Good

Nurse, Bad Nurse

Images

of nursing in literature and on screen

A Leverhulme Residency public talk. Presented on October 2nd,

2012 at the Teviot Lecture Theatre, University of Edinburgh

©Nicola White

There is an element of a blind date to these kind of

artist in residence projects – an individual and an institution are paired

together to see what each makes of the other, choreographers sent to paint

factories, poets to airports, me to you.

In my own writing – mostly short stories and memoir – I

have been interested in the conveying of emotion and in the repression of

emotion, too. Some of the work I have done has been about making stories from

real life situations. In talking to Pam Smith and Alette Willis in the run up

to the residency, we discussed the idea that emotional empathy – the ability to

imagine yourself in the place of another was something that good nursing and

good writing had in common.

But what did I really know? I never had the impulse to be

a nurse, none of my relatives are nurses and I’ve had the luck to stay out of

hospitals and doctor’s offices for the most part.

I came to realise that, like most people, many of my ideas

about nurses and nursing were borrowed from books, films and TV, and

increasingly noticed the gap between the kind of fictional nurses that stalk

the public imagination and the complex human realities of nurses in practice.

The nurse holds a potent position in popular culture –

often as a kind of superhuman figure – an angel or a devil. As we get closer, a

number of subtypes present themselves - the scolding matron, the sex kitten,

the pliant romantic heroine. A range of types that seems to me richer than that

of any other profession. Librarians, for example, may be parodied, but always

in the same shushing, fusty way, whereas the nurse manifests herself – and it

is usually herself – across a range

of characters and female archetypes. I want to explore the development of the

image of the nurse in the popular imagination and also to think a bit about

whose version of nursing we’re consuming.

It starts in the nineteenth century, a time when nursing

moves out of the home and religious institution. Before this nurses have made

various appearances in literature, but mainly as servants, nursemaids such as

the character known only as Nurse in Romeo and Juliet, more of a nanny than

what we think of as a nurse.

Charles Dickens’ Sara Gamp from the novel Martin Chuzzlewit is a different kind of

nurse. She is a professional, but also a careless drunkard, reflecting Dickens’

own view of the hired women whose nursing work was regarded as a lowest kind of

service, with money being the prime motivator. Sara drinks and takes snuff, and

steals her patient’s pillow to make herself more comfortable through the night.

She is the first bad nurse, a comic figure that Dickens created for serious

reasons. Social reformer that he was, Sara Gamp was a way of drawing attention

to the awful level of care that the sick received under untrained women who, as

Florence Nightingale put it in 1867 “were too old, too weak, too drunken, too

dirty, too stupid or too bad to do anything else.”(1)

In an essay on nursing, Dickens claimed “We English people

have among us the best nursing for love and the worst nursing for money that

can be got in Europe, though our women are all nurses born.’(2)

This idea that nursing is a natural job for a woman recurs

again and again at this time, that to care is innately female. And because of

this, there are parallels in the way the image of women and the image of

nursing change over the years.

In the same essay, Dickens makes a very interesting point

about the word nurse. In English we

use the same word for feeding an infant as taking care of the sick. It comes

from the same roots as to nourish. In other European languages, the term is

more neutral and specific – in French the verb used – infermier – means

simply to watch over the sick, in German, the equivalent is to do your duty by

the sick. Our use of the word

nursing for two purposes suggests a link between them, that on a primal level

we see nursing as domestic, familial and female.

Dickens was a great supporter of Florence Nightingale, the

women who, more than anyone, created the idea of nursing as a proper profession

through her work in the Crimea and her establishment of the world’s first

secular nursing school. She set new standards of care and a new respectability

for the women who undertook it. Florence was, of course, not a fictional

character. Her writings were impassioned and practical and her influence and

organisational powers enormous, and yet…

It seemed that society couldn’t simply admire the

intelligence and drive of Florence Nightingale for the human qualities they

were, she had to be turned into a saint, fictionalised, as it were, as the

silent Lady with the Lamp, floating through the wards of Scutari. Painting and

etchings were made, poems were composed in which Florence is portrayed not as a

very determined woman, but as a gentle disembodied Saint.

A stanza in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem ‘Santa Filomena’ tracks the effect

of her progress through the ward:

“And

slow, as in a dream of bliss

This Florence is so elevated, so lacking in physical

reality that the patient can’t even touch her hem, but contents himself with

kissing her shadow.

Even in less reverent settings, such as this Punch

cartoon, Florence and her helpers were depicted as angels and birds –

fluttering, not quite earthly beings.

An immensely practical woman, Nightingale disliked the

sentimental reverence that her name inspired. Her nursing was admired not as a

learnt skill with a basis in science, but as an expression of elevated

femininity and almost religious compassion.

The prevalent image we have of the nurse as we move into

the 20th century is the woman by the bedside, the vertical female

and the horizontal male.

And this image prevailed throughout the century, despite

the many other places apart from hospital bedsides in which nurses worked and

continue to work - in the community, in health promotion, with people with

learning difficulties or mental health problems, as teachers.

I think this is largely because of the potency of the

image of nursing within the context of war – and the attraction of this setting

for writers and filmmakers.

Examples include Vera Brittain’s memoir Testament of Youth, made into a major

television series in the seventies, centering on her wartime nursing

experience, novels by Ernest Hemingway such as A Farewell to Arms in which the love interest is a nurse attending

to the wounded of the second world war, or more recently Michael Ondaatje’s English Patient, and Ian McEwan’s Atonement.

Keira Knightley in Atonement

The settings are full of

conflict and sacrifice, sudden death and tough moral choices - catnip for

writers.

But it‘s also the case that wartime nursing is well

represented in literature because the voluntary, short term nature of the work

brought in people who were primarily writers to nursing and could write from

the nurse’s perspective.

Louisa May Alcott, for example, author of Little Women, nursed soldiers in the American

Civil War until she herself caught typhoid pneumonia, but the experiences

formed the basis of her first book, Hospital

Sketches in 1863

And we have the poet Walt Whitman, a rare example of a

male nurse, writing about his wartime nursing experience in the American civil

war, in his classic 1900 collection, Leaves

of Grass.

The poem is entitled The Wound Dresser, and this is a stanza from it.

“I am faithful, I do not give out;

It is the earliest expression I’ve found of

how care feels from the inside – that duality of outer calmness and competency

with interior emotion of the caregiver. Male nurses were common in these late

19th century conflicts. It has been argued that it was Florence

Nightingale with her all-women schooling and her motto “Every woman is a nurse”

who set the course for excluding men from nursing for almost a century.

It was in the first world war that we start to get a

torrent of imagery of nursing – in drawings, paintings, photographs, poetry,

silent films, diaries.

The flowing robes of the red cross nurse and the VADs took

the imagery of nurse back to its convent origins with the same tones of purity

and chastity.

The most powerful British account of nursing in that war

was a work I’ve previously mentioned, Vera Brittain’s memoir Testament of Youth written in1933 – she

says of nursing that ‘every task had a sacred glamour’. Nursing in this context

was a sacrifice and a duty, a way of standing alongside the brothers and lovers

who served.

Yet I think there is something more interesting going on

here, less self-effacing. Sandra M Gilbert, in a provocative article about

literature and gender in the First World War, pins down a deeper power

struggle.

“The figure

of the nurse ultimately takes on a majesty which hints that she is mistress

rather than slave, goddess rather than supplicant. After all, when men are

immobilized and dehumanized, it is only these women who possess the old

(matriarchal) formulas for survival. Thus even while memoirists like Brittain express

“gratitude” for the “sacred glamour” of nursing, they seem to be exulting in

the expertise and knowledge which they will win from their patients.” – and she

quotes Brittain again – “Towards the men, I came to feel an almost adoring

gratitude … for the knowledge of masculine functioning which the care of them

gave me.” (3)

Gilbert goes on to talk about how this knowledge gives the

nurse authority as the male patient experiences passivity and dependency.

This increase in power is reflected in this extraordinary Red Cross poster where the injured soldier is miniaturised to baby size in the

arms of a nurse depicted as 'The Great Mother’ and that dual meaning of nursing

comes back into play.

Nurses imagined by male writers often do have a kind of

sinister power. Their knowledge, and explicitly their knowledge of the male

body has emerged ever since in stories as potentially threatening.

It was perhaps inevitable that having placed nurses on

such a lofty pedestal, a counterbalance had to emerge. You can’t have an angel

without a devil, and so the balancing image of dragon nurse emerges. Some of

this reflects the view of older women as unattractive, but there is something

specifically punitive about the harridan.

Sid James and Hattie Jacques in Carry On Nurse

She is a creature of the institution,

there to crush fun and individuality She is a complement to the young ingénue,

a kind of ying and to her yang – this is most explicit in films like the Carry On … series of the fifties and

sixties. With Hattie Jacques in the role of matron, constantly policing the

rebellious games which seem to be the main focus of ward life.

In the world of Carry

On, the harridan is not a complete monster, she is a figure of fun, a

buffoonish spinster who is nevertheless allowed her own romantic dreams.

It is in American fiction that the bad nurse becomes a

more chilling prospect.

Nurse Ratched from One

Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is probably the best known nurse monster, and

although Milos Forman’s film came out in 1975, her name is still invoked,

especially in the area of mental health care. In Ken Kesey’s original novel,

written in 1962, she was known as Big Nurse:

‘The

Big Nurse gets real put out if something keeps her outfit from running like a

smooth, accurate precision-made machine. The slightest thing messy or out of

kilter or in the way ties her into a little knot of tight-smiled fury. She

walks around with that same doll smile crimped between her chin and her nose

and that same calm whir coming from her eyes, but down inside her she’s tense

as steel, and she don’t relax a hair till she gets the nuisance attended to.’ (4)

Nurse Ratched is a nurse without empathy. The need for

dominance and order are all that drive her.

In Stephen King’s Misery,

we meet retired nurse Annie Wilkes who rescues her favourite author then holds

him hostage. We have no evidence that she was a monster on the wards like Nurse

Ratched, but she is psychotic, and in a key scene, we see her use her medical

knowledge – that knowledge so dangerous in a woman’s hands – to efficiently

cripple her prisoner.

While these malevolent characters have real power and

longevity they are not as frequently encountered as the image of the sexy

nurse. An image that perhaps more annoying to real life nurses than even the

Nurse Ratched tag.

While having its heyday in the 60s and 70s, the fantasy is

still live and kicking, and any innocent google search for nurse uniforms turns

up more scanty fancy dress than practical clothing. In a novel as recent as

2006’s Christine Falls by John

Banville, writing as his pulp fiction alter ego Benjamin Black, we have the

hoary old cliché of the night nurse who can’t resist slipping into bed with the

hospitalised yet oddly irresistible narrator/hero.

In an article on the changing image of nurses in popular

culture, Phil Darbyshire and Suzanne Gordon acknowledge the complexity of the

origins of this stereotype, and the inevitable conflation of intimate body work

with a sexual interpretation for this work.

“When patients enter a hospital,” they write, “the traditional

power relations are reversed and they find themselves vulnerable and dependent

rather than strong and in control. At a societal level (for not every male

patient will see his situation in this way), one way of redressing this balance

is to metaphorically (or perhaps even practically) sexualize the encounters

between nurses and patients…The man in question may not be able to walk, or

pee, or feed himself. He may be frightened, anxious and vulnerable. But he can

pat butt or dream about it and turn the nurse who has power over him into

someone he can dominate, if not in reality, then in his fantasy.” (5)

The sexbomb nurse is a male construct, but

there is another version of the nurse I would argue is equally two-dimensional

and misguided and which is mainly created by women, for women, and that is the

romantic heroine, as she appears in traditional Mills and Boon or Harlequin

type medical romance novels.

Romance novel nurses are portrayed as ultimately

submissive women, nursing being no more than a stage on which to display their

nurturing skills to a prospective husband – usually a doctor, several salary and

social scales above them.

The career is abandoned without a second glance once the

proposal is made and the woman enters her true role of wife and mother, for

which nursing has been a rehearsal.

In fact, nurses appear in every type of novel and film,

sometimes in walk-on parts, and it wouldn’t be particularly interesting to

enumerate them all. But I want to look at one crime novel from 1971 which puts

nurses on centre stage at a time when old ideas of nursing were giving way to

new ones.

PD James’s Shroud for a Nightingale is one of her

successful Adam Dalgleish detective series and is set in a nursing school. A

student is inventively poisoned during a teaching demonstration and the police

are called in. Interestingly, Baroness James, the author, worked for many years

in an administrative role in the health service, and her knowledge of

underlying health policy informs the setting. This is a mealtime exchange amongst three nurse teachers about a fictional policy initiative:

“And now we have the

Salmon Report with all its talk of first, second and third tiers of management.

Management for what? There’s too much technical jargon. Ask yourself what is

the function of a nurse today. What exactly are we trying to teach these girls?

Sister

Brunfett said: ‘To obey orders implicity and be loyal to their superiors.

Obedience and loyalty. Teach the students those and you’ve got a good nurse.’ She

sliced a potato in two with such viciousness that the knife rasped the plate.

Sister Gearing laughed.

‘You’re

twenty years out of date, Brunfett. That was good enough for your generation,

but these kids ask whether the orders are reasonable before they start obeying

and what their superiors have done to deserve their respect. A good thing too

on the whole. How on earth do you expect to attract intelligent girls into

nursing if you treat them like morons? We ought to encourage them to question

established procedures, even to answer back occasionally.” (6)

Despite these new winds blowing through the health

service, the novel’s nurses’ home is a claustrophobic single-sex environment,

and while the characters are better drawn than in a Mills and Boon, each has

their neurotic fixation, and in one case – minor spoiler alert - a nazi past.

It is a fascinating book in terms of nursing imagery, but not exactly

uplifting.

As we move into an age dominated by television, there is

no shortage of nurses as characters in hospital soaps and dramas. However, it’s

arguable that we don’t really learn much about the job of nursing through these

programmes as the setting is there to service us with stories about characters

and relationships. The doctors and surgeons are the chief movers, and the

patients a revolving door of plot devices. Even a drama as masterly and

seemingly well-researched as ER attracted

protests from the Baltimore based Center for Nursing Advocacy.

Their objections were multiple, and could easily be

applied to a wide range of similar programmes. One was that the role of the

nurses was often reduced to ‘gurney pushing’ and attracting the attention of

doctors to emergencies, while the doctors spent an unrealistic amount of time

by their patients’ sides, undertaking tasks more usually done by nurses.

Another interesting point they made was that when the nurse characters became

frustrated with the limitations of their nursing role, they never considered

advancement within their profession, say, by taking a masters or training in a

specialism, no – the only place for an ambitious nurse was in medical school,

as happened with the character Abby Lockhart. Smart nurses become doctors was

the clear message to millions of viewers.

An interesting twist on the

prevalence of medical soaps was the 2000 film Nurse Betty starring Rene Zellweger. Traumatised by witnessing her

husband’s murder, Betty believes she is the nurse heroine in a TV soap opera,

and manages to get hired as a nursing assistant after saving someone’s life

using knowledge she gained from watching television. It’s dangerous territory,

but resonant too. I have to admit that somewhere in my head, I do believe that

given the opportunity and a suitable biro casing, I too could have a go at a

tracheostomy. How hard can it be?

It was in the 1980s that the

male nurse started to re-appear, though usually in a supporting role. The

standard image of the male nurse is someone with plenty of integrity, but who

doesn’t enjoy high status with other men. He is a girl’s best friend rather than

the romantic lead.

In the recent Meet the Parents films, accident-prone

hero, Gaylord Focker is a nurse. There is no plot reason for him to be a nurse,

it’s simply, and tellingly, a comic device, a handicap to overcome, like his name.

But even in comedy his integrity wins through, whereas a doctor character is

revealed as an unfaithful snake.

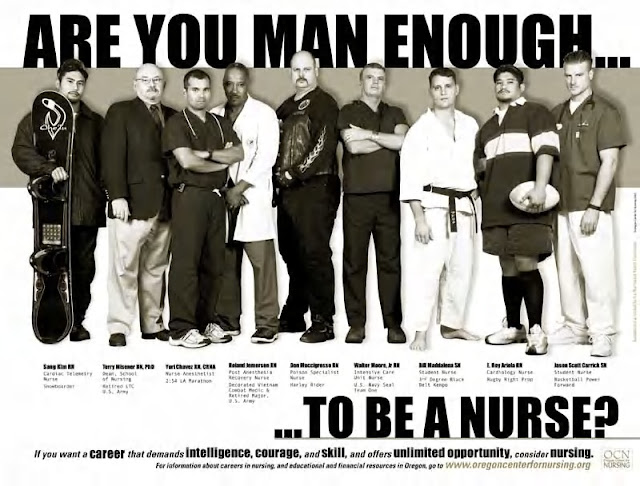

This American poster campaign is an

interesting reflection of the attempt to ‘butch up’ the image of the male

nurse, but I think succeeds only in pushing it towards a more banal kind of

male stereotype.

Which brings me to the most

recent depiction of nursing in a major series, Nurse Jackie, starring Edie Falco. I would argue that Nurse Jackie

is a new type of fictional nurse, a maverick. Jackie is the centre of the

action. She is highly skilled, and is deferred to by fellow nurses, students

and doctors. She has importance in her department in a way no previous

fictional nurse has had. She plays the role of maverick in that she has her own

moral code, rules are often broken for what Jackie deems a higher good.

She flushes away the severed ear

of an unrepentant man who has attacked a woman with a knife. In another

programme she and her fellow nurses assist the dying of a former colleague with

terminal cancer who has come to them to ask for this favour.

There is also the unfortunate

matter of her addiction to prescription drugs and what she does to get these,

but on the whole I would say Nurse Jackie is a cheering advance in the long

history of nurse representations, because she is an autonomous being. She is

smart and respected, she possesses earned knowledge and she makes decisions

within her field. And I like the way they have used and subverted the imagery

of the sainted nurse in this publicity still.

I think America has been more forward looking than Britain

both in terms of the images they produce and the vocal way in which nurse

organisations such as The Truth about Nursing lobby for more accurate

representation of nurses in the media.

In one recent posting, the website analysed the imagery of

kitsch ornaments designed as gifts for grateful patients to buy.

Aside from the crime against good taste and the

environment that these geegaws represent, the writer presents an acute analysis

of what is wrong with the underlying premise:

“Although the Truth appreciates

positive comments about nurses, we believe that the image of the

"angel" or "saint" is generally unhelpful. It fails to

convey the college-level knowledge base, critical thinking skills, and hard

work required to be a nurse.

And it may suggest

that nurses are supernatural beings who do not require decent working

conditions, adequate staffing, or a significant role in health care

decision-making or policy. If nurses are angels, then perhaps they can care for

an unlimited number of patients and still deliver top-quality care.

To the extent nurses

do seem to suffer in such working conditions, it may be viewed as merely

evidence of their angelic virtue, not a reason to alter the conditions.”

Here in Britain we seem to enjoy looking backwards as much

as forwards. The recent BBC series Call

the Midwife was a huge hit with its nostalgic, hovis-tinted view of life in

the east end of London. A scene

sticks with me in which Chummy, the new midwife brilliantly played by Miranda

Hart, calms a nervous patient, telling her that all she has to do is trust the

doctor. The patient immediately relaxes into submissiveness and the doctor

praises Chummy in high terms for this, saying she has the true makings of a

nurse. What harm, you might think? But this representation of the nurse or

midwife as handmaiden of the doctor’s will, I’m sure carries over in people’s

heads into the real world and to their encounters with real nurses.

Outdated imagery of nursing overlaps and obscures a clear

picture of todays’ nurses. Even in the Olympics opening ceremony, a thrilling

assertion if ever there was one of the centrality of nursing in British

culture. Look at the costumes. I know there was a little bit of a Peter Pan

theme going on, but still. The men get to wear contemporary looks, but we

prefer female nurses in aprons, big hats and full skirts. In the public imagination,

that’s what a nurse is.

And even though nurses have not worn caps in the NHS for

many years, the symbol on the bedside call button is a nurses cap. That is the

visual shorthand for nurse. You might consider that a trivial detail, but I

think it all points to a slippage between who nurses are and who the public

think they are.

I used to think that the phrase ‘Reality TV’

was a

pejorative term, but I would argue that the most true and useful depictions of

nurses in mainstream media are through documentaries such Channel 4’s 24 Hours in A&E where we see nurses

absorbed in a wide range of tasks, part of a team, juggling diplomatic people

skills with dextrous clinical care . They are three dimensional human beings

and highly skilled in what the do, and very committed, you can see it. And when

the camera turns to them they have interesting things to say.

Nurses from King's Hospital, London in 24 Hours in A&E

There is also the brilliant but not widely watched Getting On on BBC 4, about to go into a

third series. Created by former psychiatric nurse Jo Brand, it shows life in

what she terms an NHS ‘backwater’ – the geriatric ward – and is a deliberate

attempt to get away from the more hackneyed stereotypes. ''I wanted to do

something that was funny and sad; not glamorous with a load of young people in

it,'' Brand said. In its emphasis

on the frustrations of hierarchies and bureaucracy, it is more like The Office than Holby City, and feels closer to life. I doubt if it would attract

anyone into the profession, however.

Getting On, BBC 4, 2011

In the promotion blurb for this talk I included a

provocation – that I’d look at how far nurses might be complicit in their own

stereotyping. Well, with the exception of the last two examples, hardly any of

this imagery has been created by nurses, it has been created around them or

projected on to them.

On the RCN website on international nurses day their home

page displayed a quote from a patient’s viewpoint, describing the wonderfulness

of his nurse and ending, inevitably. ‘She’s an angel.’

In her 1983 book The

Politics of Nursing Jane Salvage argued that sometimes nurses collude in sustaining the selfless angel stereotype while

professing to scorn it. She writes, “The trouble is we are secretly flattered

by the myths, especially those emphasizing dedication and high-minded

self-sacrifice”

1983 was decades ago, yet it seems that in

cases like the RCN website, things have not moved on that much, and that

laudable initiatives like International Nurses day can easily become bogged

down in sentimentality and cliché, in things that are said about nurses rather

than in what nurses have to say.

There is a long list of doctors who have turned their

experiences into compelling stories – Anton Chekhov, Arthur Conan Doyle,

thriller writer Micheal Crichton, Khaled Hosseini, or someone like Jed

Mercurio, who went straight from being a junior hospital doctor to writing the

ground-breaking series Cardiac Arrest. There is no equivalent roster of

nursing writers, though there are a few recent exceptions such as Christie

Watson, a pediatrics nurse who last year won the Costa prize for her first

novel, or Americans Cortney Davis and Jeanne Bryner who have established

reputations as poets and encouraged other nurses to write, publishing

anthologies of nurses’ writing such as this one:

I don’t know why more nurses don’t write. Are nurses

ambivalent about writing? Are they too self effacing? Too busy?

Elsie Stevenson, the first director of nursing here at

Edinburgh, travelled through Europe during the second world war and its

aftermath and no doubt had many unforgettable experiences. She kept a diary

during this time. Here are two excerpts:

Egypt 10th May 1944 "Up all night. 15,000 more refugees – 24 admitted to hospital. Very

tired.”

Germany 26th November 1945 "Snowing. really taking hold – untold problems. Worked hard all day. To

bed late. very tired.”

Untold problems.

When I can persuade nurses away from their occupations to

talk to me, they tell me fascinating things. Their private rituals, the way

they handle emotion, the way they carry the stories of the people they have

nursed with them. The times their endurance has been tested or broken. We talk

of the emotional labour of nursing, have learned to define the work in those

terms as well as in terms of the practical and technical skills – but what is

the cost of this emotional labour? Only nurses reflecting on their own

experiences can tell us.

Early on in the residency, I came across this poem by

Cortney Davis, What the Nurse Likes –

here is a short extract.

What

the Nurse Likes

I

like looking into patient's ears

and seeing what they can never see.

It's

like owning them.

I

like patient's honesty--

they trust me with simple things:

They

wake at night and count heartbeats.

They

search for lumps.

I

am also afraid.

I

like the way women look at me

I

like lifting a woman's hair

I

like eccentric patients:

Reading it for the first time was like discovering a new

viewpoint on the world of care. It was fresh, human and unsanitised. It was

news from a place I hadn’t been before.

There is a saying in creative writing classes, to give new

writers courage. They say Who is going to

tell your story if you don’t?

And so I urge the nurses among you to tell your stories in

any way that appeals, through dairies, poems, on blogs. Discover your own

thoughts about what you do.

Nurses know nursing in a way that no one else does, and

yet the reflections you have, though often well meant, are created by others. In an address to students at Columbia University, New York in 1991, the writer Salman Rushdie emphasised the importance of articulating your own experience.

“Those

who do not have power over the story that dominates their lives, the power to

retell it, rethink it, deconstruct it, joke about it, and change it as times

change, truly are powerless, because they cannot think new thoughts."

I would add in conclusion that’s it’s not only about thinking new thoughts but also creating a

truer picture for others. And if it means taking a step down from a pedestal

to do it, the price is well worth it.

(1)Letter

from Florence Nightingale to Sir Thomas Watson, Bart, London dated 19 Jan 1867

(2)Charles Dickens, “The Nurse in Leading Strings”, Household Words 17, 1858

(3)Sandra M Gilbert "Soldier's Heart: Literary Men,

Literary Women and the Great War." in Connecting Spheres: Women in

the Western World, 1500 to the Present, ed. Marilyn Boxer and Jean

Quartaert, Oxford University Press, 1987.

(4)Ken Kesey, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Methuen and Co.,1962

(5)Phil Darbyshire and Suzanne Gordon, “Exploring Popular Images and Representations of

Nurses and Nursing” in Professional Nursing: Concepts, Issues, and Challenges, Springer Publishing Company, 2005

(6)PD James,

Shroud for a Nightingale, Faber & Faber, 1971

Even in less reverent settings, such as this Punch cartoon, Florence and her helpers were depicted as angels and birds – fluttering, not quite earthly beings.

I think this is largely because of the potency of the image of nursing within the context of war – and the attraction of this setting for writers and filmmakers.

|

| Keira Knightley in Atonement |

|

| Sid James and Hattie Jacques in Carry On Nurse |

She is a creature of the institution, there to crush fun and individuality She is a complement to the young ingénue, a kind of ying and to her yang – this is most explicit in films like the Carry On … series of the fifties and sixties. With Hattie Jacques in the role of matron, constantly policing the rebellious games which seem to be the main focus of ward life.

In the world of Carry On, the harridan is not a complete monster, she is a figure of fun, a buffoonish spinster who is nevertheless allowed her own romantic dreams.

Sister Brunfett said: ‘To obey orders implicity and be loyal to their superiors. Obedience and loyalty. Teach the students those and you’ve got a good nurse.’ She sliced a potato in two with such viciousness that the knife rasped the plate. Sister Gearing laughed.

‘You’re twenty years out of date, Brunfett. That was good enough for your generation, but these kids ask whether the orders are reasonable before they start obeying and what their superiors have done to deserve their respect. A good thing too on the whole. How on earth do you expect to attract intelligent girls into nursing if you treat them like morons? We ought to encourage them to question established procedures, even to answer back occasionally.” (6)

was a pejorative term, but I would argue that the most true and useful depictions of nurses in mainstream media are through documentaries such Channel 4’s 24 Hours in A&E where we see nurses absorbed in a wide range of tasks, part of a team, juggling diplomatic people skills with dextrous clinical care . They are three dimensional human beings and highly skilled in what the do, and very committed, you can see it. And when the camera turns to them they have interesting things to say.

|

| Nurses from King's Hospital, London in 24 Hours in A&E |

There is also the brilliant but not widely watched Getting On on BBC 4, about to go into a third series. Created by former psychiatric nurse Jo Brand, it shows life in what she terms an NHS ‘backwater’ – the geriatric ward – and is a deliberate attempt to get away from the more hackneyed stereotypes. ''I wanted to do something that was funny and sad; not glamorous with a load of young people in it,'' Brand said. In its emphasis on the frustrations of hierarchies and bureaucracy, it is more like The Office than Holby City, and feels closer to life. I doubt if it would attract anyone into the profession, however.

|

| Getting On, BBC 4, 2011 |

What the Nurse Likes

It's like owning them.

I like patient's honesty-- they trust me with simple things:

They wake at night and count heartbeats.

They search for lumps.

I like eccentric patients:

As an ICU nurse, I found Echo Heron's "Intensive Care" very realistic. I am also about to read "Get Well Soon! My (Un)Brilliant Career as a Nurse" by Australian Kristy Chambers (University of Queensland Press, 2012).

ReplyDeleteThis is the blurb:

"If you thought TV’s Nurse Jackie told it like it was, then Get Well Soon! is one hell of a revelation.

"Falling into the nursing profession, Kristy Chambers has spent almost a decade working as a nurse, with patients ranging from drug addicts through cancer patients to those in Emergency. Along the way she met some wonderfully brave people. As for others, well, you’ll need to read her book to really believe it.

"Chambers is a new and idiosyncratic voice in memoir writing. Her tone is dark, her humour black, but there is honesty, heart and compassion in Get Well Soon! She shows us more than ever the incredible work done by nurses and the challenges they face."

Hear Kristy speak about her memoir

http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/lifematters/get-well-soon3a-kristy-chambers/4235966

Hello Philip,

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for your comment - have enjoyed your writing and its stirring articulacy was very useful in the formation of this talk. Time for all nurses to speak up , I agree.

Will keep in touch,

Nicola

Nice article, pleasure to read your blog.I am a retraited nurse.

ReplyDeleteExcellent! As a nurse and a librarian, working in a college of nursing, I appreciate your words so much. I spend a lot of time working with the students to prepare writing assignments. Most of the students just dread these assignments. Partly because the assignments are tedious and partly because the students do not like to write; they feel inadequate for the rigors of technical writing. There are few outlets for creative expression in nursing college. And yet the practice of painting, writing, drawing, creating relieves so much stress and it is not taught to the students.

ReplyDeleteAnd in the end, the students do not tell their stories. Most never will. Thank you for the encouragement.

Brilliant! A very useful cultural and nursing resource. Also appreciate the inclusion of male nurses in the media and history too and the challenges of where nursing will be globally over the next few decades amid self-care and when demographic trends become reality - which they are as we write...

ReplyDeletehttp://hodges-model.blogspot.co.uk/

Hodges' model: a reflective resource for past, now and Nursing's tomorrows

Excelent post! I´m a spanish student of nursing and I like very much.

ReplyDeleteI'm a nurse and I write. And yes, I also write about nurses, fictionally of course. My new novel, An Angel's Alternative is a about nurses, mostly male, and the choices they face. I hope any nurses that read it would find it true to life, and hopefully anyone who reads it will find it entertaining, and perhaps a little eye- opening. If it's not being too self- promoting, here's the link http://www.amazon.co.uk/An-Angels-Alternative-ebook/dp/B00B3GVKAY/ref=pd_rhf_pe_p_t_1_S371

ReplyDeleteI remember how the cna's we know right now all started during world war 1. I really appreciate how it all started.

ReplyDeleteThink you missed Nurse Diesel (Cloris Leachman) from the Mel Books movie 'High Anxiety'!

ReplyDeletehttp://moviecappa.files.wordpress.com/2012/07/nursenoir_nursediesel4.jpg

The ultimate nurse R&R?

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x1545jk_bo-diddley-pills-1961-digitally-remastered_music

I am grateful for the work you did to put this together. I Googled for "nurse stories" hoping to find exactly this kind of information.

ReplyDeleteAfter finding in a junk store last week, I just finished reading "A Girl in Ten Thousand" (1896) by L.T.Meade (pseud of Elizabeth Thomasina Meade Smith, 1844–1914). I was amazed to see the nurse suggesting a therapy to the MD who gladly and successfully applies it, nurse then thinking "I believe I have conquered [the disease in this child]". The training hospital is intent to forestall any intercourse (even verbal) between nurses and MDs, to vouchsafe "the new ways in which things are done in London hospitals". Nursing has become a "profession" and a "noble profession". The hopes were then as they are now.

I was surprised to find no mention of the Cherry Ames series of stories in your survey.

Thank you again for this superb overview of nurse stories.